Sun Paper Article

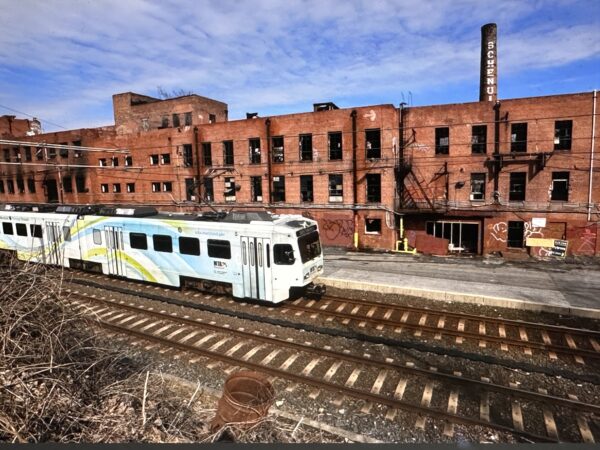

Ever since Frank G. Schenuit opened his Double Grip tire factory in 1925, his name has been associated with a campus of industrial Woodberry buildings.

Though the rubber works closed decades ago, he left a lasting legacy when he had his name spelled out in bricks on the plant’s landmark chimney.

The interior of the plant he built, a place that turned out thousands of aircraft tires during World War II, was largely destroyed by a fire Thursday night.

While other of Woodberry’s industrial buildings have been converted to other uses, the old Schenuit property failed over the years to become apartments or a restaurant.

The Schenuit story began in 1912, when, as a young man, Frank Schenuit started making tires for racing motorcycles.

Schenuit had a tire shop at 1200 Mount Royal Ave. at Dolphin Street, just opposite Mount Royal Station. His original sales operation later became an artist supply store that was patronized by Maryland Institute College of Art students.

In 1921, after selling tires and auto accessories, Schenuit patented a non-skid pneumatic tire he called the Double Grip.

According to Baltimore Sun articles, he wanted to make his own tires, and by 1925 Baltimore’s Mayor Howard Jackson as well as officials of the old State Roads Commission and the Maryland Motor Vehicles Commission were admiring Schenuit’s new Woodberry plant.

He bought a former Woodberry cotton mill, a gray fieldstone structure built in the 1840s that once made the heavy cotton duck used in ship’s sails.

The Sun’s account of the tire plant opening described the Pennsylvania Railroad’s tracks that ran alongside the building, making it easy to ship in raw materials and ship out tires. “Two huge steam boilers, of 210 horsepower, deliver the steam for the curing process,” The Sun reported, adding that the water for the steam came from the adjoining Jones Falls.

The plant initially employed 100, but that changed as Schenuit’s sales increased.

He was forced to rebuild his whole operation in late 1929 after a major fire destroyed the plant. The Sun said that the flames were visible all over the city and that 10,000 people assembled to observe the blaze.

The brick structure that burned this week was the 1930 building that replaced the old fieldstone mill.

Schenuit advertised “direct factory prices” and pledged that “every Schenuit tire is made in Baltimore,” urging his customers to “patronize local industry and help Baltimore prosper.”

The plant went into overdrive during World War II, as did other foundries and industries along the Jones Falls Valley. Schenuit complained to news reporters that while engaged in defense work — making military aircraft tires — his workforce was forced to shut down one night in 1943 during a test blackout. An air raid warden arrived at his plant’s front entrance and ordered everyone out. Schenuit protested and called the Northern police station, then on Keswick Road in Hampden. He was told, “Sorry, we can’t help you. It’s the law,” according to news accounts.

He didn’t give up easily that night. He showed a reporter how the Mount Vernon Woodberry mills (which turned out military canvas) were not forced to shut down, while Poole Engineering and Balmar, then secretly engaged in parts of the Manhattan Project, were forced to close down temporarily. Schenuit vowed to put his workers on double-time the next Sunday to recover the lost production.

Toward the end of the war, he supervised another extension of his plant to keep up with demand. The plant was then running three shifts a day and had the biggest backlog of orders in its history. The demand did not last. Sales plummeted after the war.

Schenuit, who lived in a brick Charles Street mansion in Guilford, died in March 1948. He is buried in New Cathedral Cemetery.

His family continued operating the business through the end of the 1970s. photo below

John Payne, in his comprehensive 1798 tome, A New and Complete System of Universal Geography, noted the flouring mills along the Jones Falls near Baltimore. At the time, wealthy abolitionist Elisha Tyson owned two of the ten documented mills: one at the location of what is now Mill No. 1, and another in Woodberry. The Woodberry mill is described as a “handsome three story building, the first of stone and the other two of brick” that “can grind at least eighty-thousand bushels a year.”

Tyson’s Woodberry gristmill sold to Horatio Gambrill, David Carroll, and their associates who expanded the structure into a textile mill they called the Woodberry Factory. It was the partnership’s second venture in the area after buying and converting Whitehall gristmill (just south of their new factory) for textile production in 1839. The mills manufactured cotton duck, a fabric primarily used for ship sails during a time when clipper sailing ships dominated local trade. Through the low cost of raw cotton cultivated with enslaved labor and an ability to attract workers despite lower wages than competing mills in the North, the mills along the Jones Falls cornered the market. Their largest buyers were in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. They also found markets overseas in British provinces, South America, and England.

The Woodberry Factory was a purely functional building: a long, three story building designed to maximize daylight and accommodate the machinery powered by horizontal line shafts. A clerestory roof provided more light. Each floor housed machinery for a different step in the manufacturing process. A central stair tower was topped with a dome shaped bell tower. The bell rang on a schedule to call nearby workers to the factory for their shifts.

The new textile mills required a large workforce and this large workforce needed homes. To this end, owners erected mill villages close to their factories. Woodberry began as a string of Gothic Revival duplexes built of locally quarried stone and resembling country cottages. The homes included yards for growing produce, raising livestock, and planting flower beds. Gambrill erected a church in the village. A school was also built, although it was common for children of mill workers to drop out early to work in the mills and help support their families. In 1850, an all-in-one general store, post-office, and social hall was constructed near the railroad tracks.

Additional structures went up as operations grew and new technologies emerged. When the factory started using steam power in 1846, a boiler house was built on the side facing the Jones Falls. The factory acquired a fire engine some time before 1854; a shrewd acquisition considering the tendency for factories full of “cotton-flyings” (or fuzz) to catch fire and burn. The most significant addition to the site was Park Mill, built in 1855 to produce seine netting for fishing boats.

By the turn of the twentieth century, most of the mills in the Jones Falls Valley were brought under a national textile conglomerate, the Mount Vernon-Woodberry Mills. In the 1920s, the company began shuttering the mills in favor of its plants in the South. The Woodberry Factory was sold to Frank G. Schenuit Rubber Co. in 1924. In 1929, a six-alarm fire destroyed the building. Residents across the tracks had to evacuate their homes and the blaze was large enough to attract a reported crowd of 10,000 people.

Schenuit manufactured truck and automobile tires, and later manufactured aircraft tires for the military during World War II. The company became dependent on government contracts and nearly went bankrupt after the war. By the 1960s, the company began expanding into the home and garden industry 5by buying out smaller manufacturers that made wheelbarrows, industrial wood products, lawn equipment, exercise equipment, and lawn and patio furniture. By the 1970s, Schenuit had moved out of the tire business. In 1972, after Hurricane Agnes, Schenuit sold the Woodberry plant to McCreary Tire and Rubber Company. McCreary closed down just three years later when the company laid off all of the plant’s three hundred workers.

Park Mill sold in 1925, and over the next four decades, the mill was used by a variety of companies including the Commercial Envelope Company and Bes-Cone, an ice-cream cone manufacturing company established by Mitchell Glassner, who invented one of the early machines for that purpose.

Today, Park Mill is leased to a number of small businesses. The Schenuit factory remains empty after yet another fire, one of the only major industrial buildings in the Jones Falls Val